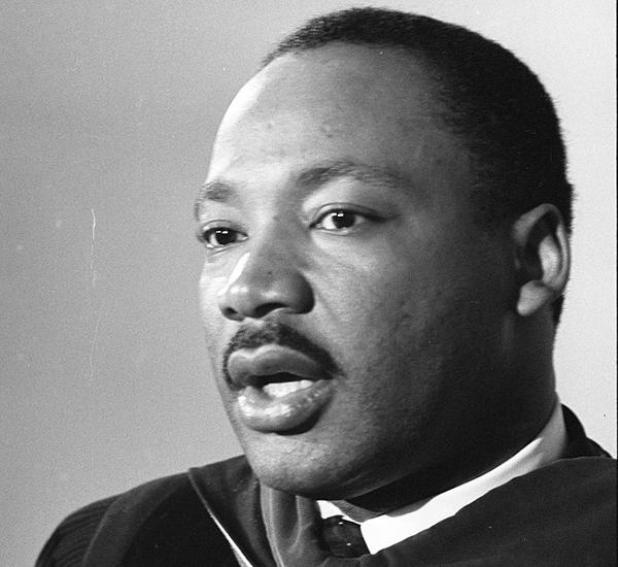

Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at a press conference in 1965. While visiting Memphis, Tennessee, to support a strike by black sanitation workers, on April 4, 1968, he was shot and killed by escaped convict James Earl Ray, sparking unrest and debate across the country. — Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-49864

Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 slaying left a nation divided and a dream in peril

The evening of April 4, 1968, found presidential hopeful and New York senator Robert F. Kennedy preparing to break the news of an ongoing national tragedy to a predominately black, poor neighborhood in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Just hours before, Kennedy had learned of the assassination of civil rights movement leader Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee. The latter was standing on the balcony of his motel room when he was shot and mortally wounded by a gunman who was, at that time, still at large.

At 7:05 p.m., Memphis time, King was pronounced dead. According to historian Thurston Clark, on hearing of King’s death, Kennedy buried his face in his hands.

“Oh God,” he said. “When is this violence going to stop?”

Four and a half years earlier, Robert’s brother and former president John F. Kennedy had been fatally shot while riding in a motorcade in Dallas. In a brutal coincidence, Robert himself would be shot and killed just months after his appearance in Indianapolis.

Taking the stage, he shared the news that was already sending the country into convulsions. Some audience members screamed, while others burst into tears.

“I have some very sad news for all of you and, I think, sad news for all of our fellow citizens and people who love peace all over the world,” he said. “And that is that Martin Luther King was shot and was killed tonight in Memphis, Tennessee.”

Despite being warned against speaking in Indianapolis, where campaign aides predicted a race riot, Kennedy’s speech is credited today for sparing the city from a wave of racially charged violence that swept the country following King’s death.

In the days to follow, more than 100 American cities descended into chaos, as law enforcement clashed with furious protestors, many of whom came from the disaffected black communities that King worked to empower.

In Washington, D.C., where black residents experienced police harassment, low employment and a de facto policy of segregation that led to substandard housing and underfunded schools, riots led to 13 deaths, hundreds of businesses damaged by looting and arson, and thousands in police custody.

Meanwhile, civil rights leaders struggled to reconcile King’s vocal pacifism with the fact of his sudden, violent passing. King’s widow, Coretta, remained in Memphis, where she led a silent march including a group of striking sanitation workers that King had come to the city to support.

In middle America, King left a complex legacy in the immediate aftermath of his death. Some saw him as a champion of civil rights, while others saw him as encouraging lawlessness and being responsible for the ongoing riots.

King’s assassination was addressed in a letter to the editor in the April 11, 1968, edition of The Holyoke Enterprise. It criticized the country’s mourning for his death.

“Have we as a nation gone completely mad?” the Holyoke resident wrote. “Before his death, the man was a rabble-rousing lawbreaker. Does the manner of his death put him above the G.I. who has given his life for his country? Apparently it does. In the name of common sense, let us put the death of Martin Luther King in proper perspective and stop this childish nonsense of enshrining him as a national hero.”

This letter sparked four others also reacting to the assassination of King. Some were sympathetic to King and his cause, while others attacked his promotion of civil disobedience.

“What you felt was an insignificant burial was, to millions of Americans, the entombment of an all-important ideal,” another Holyoke resident wrote, directly responding to the author of the April 11 letter. “Dr. King was the personification of a certain group of beliefs, among which were Christian benevolence and democratic justice. [...] A parallel, which I hope answers your question regarding servicemen, would be the burial of the unknown soldier as a symbol of the suffering in World War II.”

An April 25 letter, also from a Holyoke resident, quoted black conservative author and journalist George Schuyler, who suspected King’s motives in visiting the Memphis strikers.

“It was Dr. King’s determination to influence the course of an ordinary labor dispute by his presence that led him to Memphis. The recent rioting, vandalism and casualties were a result of this march. Labor disputes should be handled by officials of the AFL-CIO and the employers concerned, and not by demagogic outsiders with appeals to racial passion.”

The last letter printed encouraged the author of the first to imitate King’s strategy of civic involvement and “get us a badly needed historical museum, fix up Dr. Means’ tourist attraction, get some industry to Holyoke and put Holyoke on the map.”

All in all, the riots following the assassination of King led to the deaths of 43 people. In 2018, Peter Levy wrote that the backlash following King’s death constituted the “greatest wave of social unrest since the Civil War.” Martial law was declared and the U.S. military deployed in multiple cities to supplement local law enforcement, leading to occupations that lasted weeks or months.

By 1983, King’s legacy as a peace activist, human rights champion and foremost leader in black Americans’ struggle for civil rights was recognized with the adoption of Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a federal holiday, which is celebrated annually around the time of King’s birthday — Jan. 15, 1929 — rather than the date of his death.

However, his legacy should not be understood without looking at the upheaval and violence that continued especially after and as a result of his death.